It began in September 2015, when the image of a lifeless Syrian boy, Alan Kurdi, lying face down on a beach was repeatedly distributed in print and digital media. It gripped me like no other image of a bombed out building or overcrowded refugee boat had done. It put the plight of the millions of Syrian refugees front and center in my consciousness.

Little Alan Kurdi was my wake-up call to start paying attention to the world outside of myself and my work. (You can see the photo here.)

Up until that day, my studio practice had been a place of refuge and solace from the all-consuming job of starting up Now + There. Creating new works for the “Sidewalk Series,” a critique of real estate development in my Boston neighborhood, is a sensual thrill for me. I get to steal bits of public property – cast off pieces of asphalt and concrete – and make luscious green and gold worlds with them. The making process is slow and seductive, like painting, but in a manageable size and format. And playing developer is a fun fantasy.

That changed as I looked at Alan. At that point I was preparing for two career stretches, one to develop a curriculum for a 200-level course at Connecticut College, which became Shelter and Comfort, and the other, to develop a Sanctuary Series workshop for the Isabella Steward Gardner Museum’s experimental program to activate the senses, rejuvenate, and inspires.

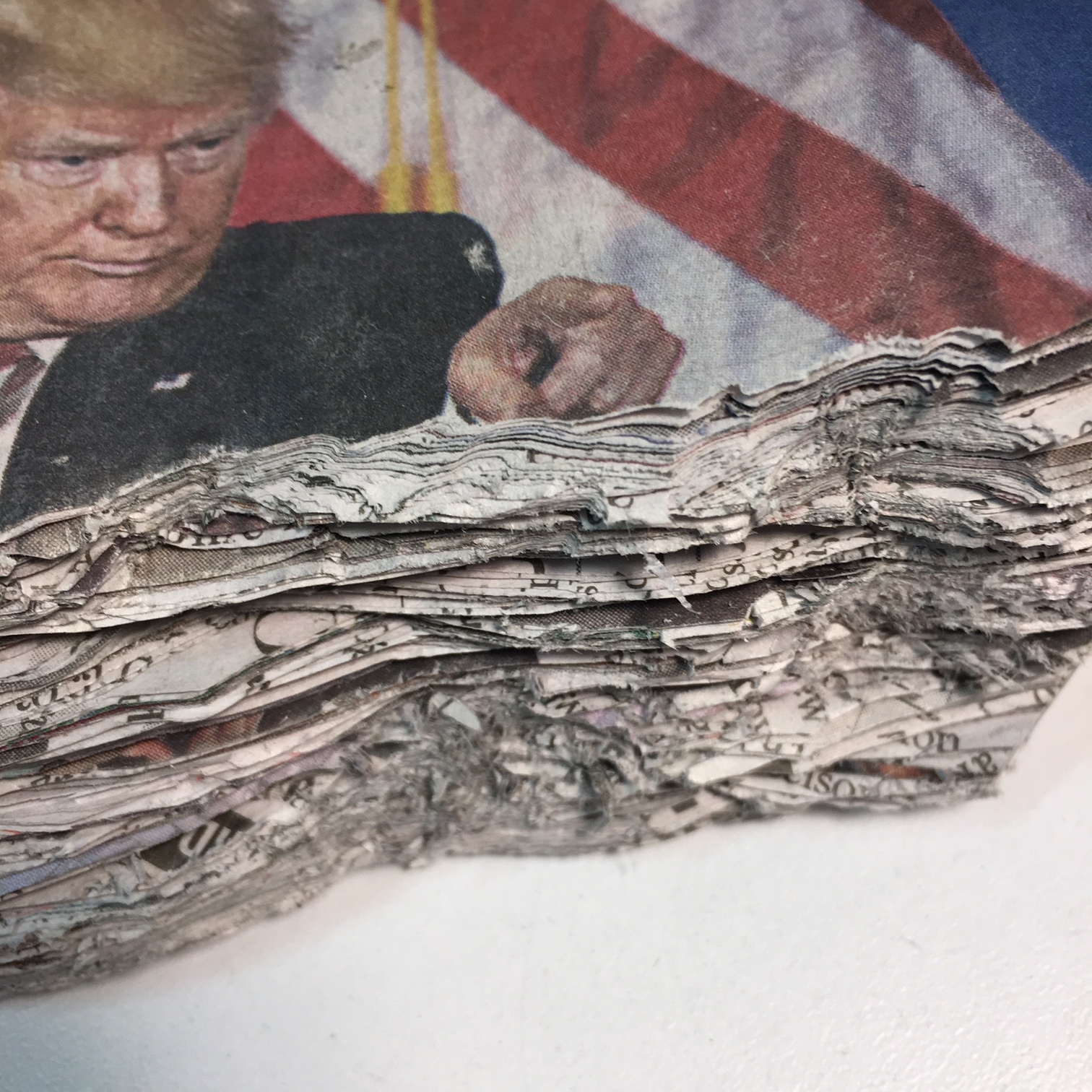

This is one month’s worth of Friday, Saturday and Sunday issues of the Boston Globe and New York Times. One step away from hoarding?

For the Gardner proposal, I used the opportunity to explore the proliferation of violent imagery in print and broadcast news through the co-creation of an object, a mandala with hundreds of violent images selected by participants. That workshop and another subsequent one at Babson College chapel have opened up a new direction in my practice. I can’t throw away newspapers!

Seriously. After the workshops, I continued reading the papers and instead of getting stuck on a horrific photo, pouring over its gory details and not being able to move on, I could see the violence and read about it. After this 14-month practice, I’ve become slightly less shocked, more desensitized. And just in time.

With the violence manifesting in our country via vicious hate speak, the entire paper is full of viciousness. The printed word is taking on power I’ve never seen in my lifetime. Now, I’m taking in the entire paper and scrutinizing it and I feel compelled, like before, to make something with it.

I take it in with my eyes, brain, heart and with my hands. I cut it into hundreds of small shapes, glue them together and form something new, a sculptural object that fits in my hand. One daily paper can fit inside my hand. It seems digestible that way. It feels powerful. It's almost like a weapon.